While architecture deals with the present and the future, archaeology delves into the past. When the two join forces, it can become an exciting venture. That is what happened recently on a hill in northern Israel. CAD and other technical “assistants” were there as well, helping to puzzle out the work of ancient planners and builders.

While architecture deals with the present and the future, archaeology delves into the past. When the two join forces, it can become an exciting venture. That is what happened recently on a hill in northern Israel. CAD and other technical “assistants” were there as well, helping to puzzle out the work of ancient planners and builders.

Archaeology is one of the primary sources of urban planning. While outlying architectural history, archaeologists need to have the ability for spatial thinking, and for understanding structures. Students of archaeology, unlike students of architecture, are not trained to meet such criteria. That is why there is often a field architect as a member of an archaeological team, especially in cases when more remarkable building remains are to be exposed.

Aaro Soderlund and Osku Soderlund, a father and son team from Finland, were invited by Professor Shimon Dar, head of the Department of Land of Israel Studies at Bar Ilan University to serve as the architects on an excavation site on the Carmel Mountain Range near the city of Haifa. Architect Aaro Soderlund serves as teacher and researcher at the Helsinki University of Technology. Osku Soderlund works at MicroAided Design Ltd. on ArchiCAD support.

As tools, the architects chose to take along the Apple PowerBook G3 equipped with 64 megabyte memory plus 5-gigabyte hard disc. The program chosen was ArchiCAD, with a GraphicConverter, PhotoShop, Playback, MoviePlayer and QuickDraw 3D Viewer. The camera they used was a digital Sony Mavica MVC-FD7 10x. In addition, they used a scanner and a printer.

The Carmel means God’s vineyard. The Byzantine period (330-636 CE) farmers cultivated wine and olive oil in these regions. Mountain slopes and wadis were terraced to maximize sun and soil conditions. Erosion provided the fertile soil from the mountain forest to the edge of the sea.

The Mount Carmel site the Finnish team came to document had once been a Byzantine local Villa Rustica. It included the ruin of a mansion with its grounds. It is located in the ancient village of Rakit, on a hill ca. 390 m above sea level, 7kms from the natural harbor of Atlit. Natural harbors are rare on the eastern shore of the Mediterranean. They served as a focal point for settlements and foreign commerce during the past 3,500 years, in which major sea trade has been conducted in this area.

From the village of Rakit one has eye contact with Atlit.

Prior to electronic communication, eye contact was one of the significant factors in deciding on the location of a settlement. At one time, the distance for eye contact could measure as much as 200 kms. Today, with the air in the Mediterranean area hazy and smoke-filled, one is lucky to be able to see at a distance of 10kms. The site is situated in the midst of a forested tract, which prevents visibility of the entire area.

In this particular case, CAD helps toward better understanding of ancient topography and of the original relationships between the various old sites, not least between military installations.

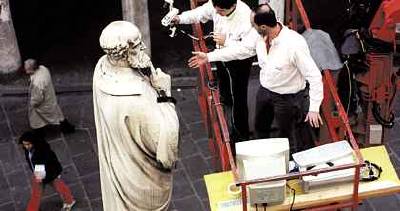

Documenting the project

The assignment of the Finnish team working in the Mediterranean sun was to document results of the Rakit springtime dig.

The Rakit mansion was found to be divided into 30 areas, 4 of which were selected for the dig. Each of these was conducted by a field supervisor plus a 10-man team.

The Rakit mansion was found to be divided into 30 areas, 4 of which were selected for the dig. Each of these was conducted by a field supervisor plus a 10-man team.

A residential quarter was found to be dispersed on an area of a hektar. Also examined were a close-by quarry, 2 burial caves, a garden, terraces, an olive press and a wine press. A map on a scale of 1:600 was prepared, revising an existing map. A road map was readied with theodolite, after which the protruding building remains were marked. These known coordinates were used as base marks for measurements, drawings and digital photography.

The digital camera was a very quick and handy tool; there was no need to wait for the development of photos. Pictures could even be taken in near darkness. The camera charge lasted up to 2 days. The only drawback was the flash, which was too powerful.

“One of our peak moments,” says Aaro Soderlund, “was when we found a previously unknown burial cave, and minutes later we were able to present the archaeologists with the digital images on screen of the particulars of that cave’s interior.”

On one standard floppy disc the architects were able to condense 20-30 JPEG images with a resolution of 640x480DPI. After having transferred the files to the PowerBook, the floppy discs were retained as back-up. The pictures were renamed according to the uniform coordinates used at the dig: A12, L215, W4, n (area, locus, wall, north). In cases where the color shading of the picture needed to be adjusted, artifacts, like, for example, the mosaics, turned out in more glowing colors than in the original – this made it easier to trace the details of the patterns and decorative designs.

As the photography was carried out at different stages of the operation – before, during and even after the dig was covered up, a series of pictures could be produced depicting each area and every uncovered item. Help for producing the final report was available since the key photos could be attached immediately to the notes of the dig – and this while digging was still going on.

Based on the accumulated drawings and photos, the team prepared 3-dimensional models using ArchiCAD:

- the entire environs of the 1,3km2 site

- the one-hektar residential quarter

- one burial cave

Modeled walls, dug up levels and other installations and artifacts were also named according to the uniform coordinates. This enabled the use of the CAD model in coordination with the notes and photos.

“The models I develop,” explains Soderlund, “are tools to understand, first of all, what was uncovered, and secondly, to interpret the finds, to formulate hypothetical reconstructions. The idea is that then the archaeological team can check to see whether the hypothesis was correct. It’s like playing tennis, the ball – the information – goes back and forth. Hypothesis and finds – each feeds the other. When new finds are discovered, the model is updated and new hypotheses are formed. The model (which clearly differentiates between evidence and hypotheses by being marked in different colors and layers), gives the archaeologist ideas what to look for and where – all this referring to architectural fragments.”

Results in Various Formats

The models of the dig were produced on 3 different formats: pictures, animation and the virtual model. All this was a prerequisite for funding. The vivid, colorful illustrations are useful in understanding the finds as well as in inviting funding.

With the ArchiCAD Alphachannel a feeling for the authentic texture could be created. In these cases, material textures received 3-D shadings. Artificial material textures were developed and changed, while manipulating the parameters, and they, as well as the original textures were also photographed directly in situ. By manipulating these values, the team was surprised to see that artificial means produced more authentic results than conventional photography.

“To obtain drawings almost immediately, clear line drawings were used, from which all uncertain information was eliminated. Base sketches were known to the archaeologists, but when we also produced angled drawings – that was new to them.

“To obtain drawings almost immediately, clear line drawings were used, from which all uncertain information was eliminated. Base sketches were known to the archaeologists, but when we also produced angled drawings – that was new to them.

“Previously,” continues the Finnish architect, perspectives became available to archaeologists only months after the dig. Now they could see them while they were still in the midst of conducting the excavation. This gave them the possibility to argue and check the questionable places.”

The final pictures were produced based on the accumulated information from the whole dig. All the attributes in these pictures were combined.

Animation provided the possibility of telling the story in a sequential fashion. In animation, the viewer does not have control of the movement, timing and order, since all that has been determined by the film director. However, animation is a useful medium in presenting the dimensions and content of a previously unknown site, e.g. for a virtual traveler.

QTVR (QuickTime Virtual Reality, a public domain on Apple, also available for PC’s) offers a very maneuverable solution compared to the VRML models, (Virtual Reality Modeling Language), where the target can behave quite unexpectedly, suddenly turning into a haphazard position. On the other hand, QTVR’s horizon remains stable and you always know where you are. Moreover, QTVR requires only a fraction of the storage space compared to VRML, let alone the power needed for calculations. The QTVR can be created easily, even from the photographs. Combined with animations, it offers a vivid picture of the authentic environment. One of QTVR’s drawbacks is that it is not strictly speaking a virtual model, but, rather, a series of interlinked 360 degree dioramas. Despite this, the system is remarkably efficient.

ArchiCAD was chosen, according to Soderlund, because it is based on object libraries that fit well with the way archaeologists code their finds, and because it is wholly 3D, easy and fast.

“The instant creation of the virtual models in situ may have been the toughest among our activities. For the students in the excavation crew it was fascinating to get acquainted “virtually” with the tomb of Marianus (a common name in this area) which we had modeled on the basis of old documents, without ever visiting it in reality.

A number of archaeologists visited the excavation site and witnessed the work. Our Demos in Israel and Finland generated offers for cooperation from a number of countries – Israel, Jordan, USA, Canada, Finland. Graphisoft, the Hungarian producer of ArchiCAD, asked to have the material for Demo use.

“The tools and programs deployed during our trip were a source of delight to us,” Soderlund concludes. “Our arsenal had plenty of capacity even though it occupied the mere space of our backpack. It seemed to us that the results were not less impressive.”

ArchiCAD

QuickTime Virtual Reality

SONY Mavica digital camera

Photoshop

Images by kind permission of Aaro Soderlund