In a recent conversation with my good friend and past teacher Robert Gill (Rendering With Pen & Ink) we discussed the value of hand drawing in an age where computer-generated drawings are the standard means of architectural communication. It was quite by pleasant coincidence them to discover that this issue was being discussed at length in another forum on ArchDaily and that there seemed to be some agreement on fundamental ideas.

In the architecture world, there are a handful of persistent debates that arise time and time again…. one of the most enduring arguments in architecture- especially in the academic sphere – is the battle between hand drawing and computer aided design. Both schools have their famous proponents: Michael Graves, for example, was known as a huge talent with a pencil and paper, and came to the defense of drawing in articles for the New York Times, among others. Patrik Schumacher, on the other hand,is famous for his commitment to the capabilities of the computer.

One of the most surprising things we discovered in reading our readers’ comments was that, despite the often heated nature of this discussion there was a surprising level of agreement among our readers. Almost all seemed to believe that CAD and hand drawing could perfectly coexist, as most seemed to feel that sketching was an ideal tool for forming ideas and design software was more suited to the precision and clarity that is required at the later stages of the project. It is worth noting, however, that almost nobody who expressed this opinion addressed the topic of hand-drawn technical drawings – which perhaps leads us to infer that when it comes to technical drawings, the computer has well and truly won.

I think that drawing in an educational setting serves a different purpose than drawing in a working office. To me, the previous is about learning to see. First year students specifically, tend to “see” a building very simply; however, once they have to reproduce what they see by hand, they start to understand the intricacies a building and its parts. They see the depth of a three-wythe masonry wall, the “lines” of the window frame, or a soldier-course reveal that provides depth and shadow. Sketching and drawing in the first year (along with building physical models) provide so many “ah-ha” moments, that it should be mandatory.

For me, sketching in the office is used when I run into the limitations of the software (or my perceived limitations of it). I get out the trace when I need to “let a line go for walk.” Sketching allows me to quickly rethink things, just to see if it is worth doing in the computer.

Some points taken from this article and by talking with Bob can be crystallized thus;

- To be able to draw you first need to be able to see, at least a little bit. In time drawing and “seeing” are simultaneously developed skills. The more you practice and the better you get at drawing, the better you get at seeing too.

- Drawing helps you understand what you are seeing and the better you understand what you see the easier it is to draw. The better understanding you have of structure for example the easier it will be to draw a building. the better an understanding of anatomy, the easier it will be to draw a draped figure.

- Drawing (like writing) is tightly bound to thinking. One needs to think while drawing. Every mark is a 2D symbol of some aspect of the 3D subject and has meaning and significance. Marks without purpose cloud the communicative power of the drawing.

- Drawing frees the mind and allows it to go where it may.

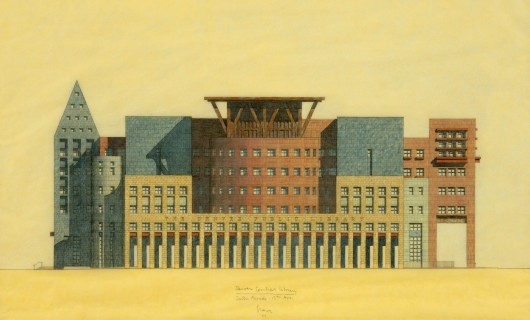

- There are scientific and emotional aspects to drawing that enable drawings to communicate feelings as well as ideas. Everyone of us has at some time admired and lingered over a beautiful architectural drawing even though the practical aspects of the design may not have reached the same degree of enchantment.

Professional opinion indicates that there is certainly a strong case for developing hand drawing skills in student of design – architectural and engineering.

See full story on archdaily.com

[amzn_product_inline asin=’0500680264′]